5 habits of innovative councils

This year, LOTI is running workshops with a number of London borough leadership teams who want to understand where and how innovation can play a role in meeting their challenges.

In those sessions, we’ve been road-testing our narrative around five key habits that councils need to practise if they are to navigate change effectively. Those habits affect all staff, but leadership teams have a huge role to play in making them possible in their organisations.

Below, I describe each in turn and welcome your feedback.

1 – Don’t guess, experiment

Local authorities are tasked to deal with almost baffling levels of complexity.

I invite you to try to think of any other type of organisation the size of council that has to provide hundreds of completely unrelated services, meet more than 1,000 statutory responsibilities and deal with some of the most thorny issues in society. The problems councils are tasked to address, from managing spiralling demand for social care to tackling climate change are inherently complex, with hundreds of variables outside any council’s control or visibility.

What’s the ideal response in the face of this level of complexity?

I suspect it’s not to write a big strategy, set out all the solutions to be implemented and then design a huge programme to deliver them. Yet this is a common approach in our sector.

Instead, I think we need to encourage a different approach. One that encompasses 3 steps.

First, admitting that we don’t know the answers. This can be extremely challenging in local government, where we encourage domain specialisation early in careers and expect senior staff to have all the answers. But – for the reasons set out above – that expectation isn’t at all reasonable. Which local authority anywhere in the UK do we think has the complete answer to these huge issues? Admitting we don’t know is not an admission of failure. It takes bravery. But it’s surely the only rational response.

Second, ask: “What if?” Instead of asking for answers from their colleagues, local government leaders should see their role as enabling their staff, residents and other partners to pose and share their hypotheses on how to make any given situation, function or service better (“What if we enabled more local residents to provide care to their neighbours?”; “What if we provided X information to households on their retrofit choices”, etc).

Third, try the smallest possible experiment to test each “what if”. Leaders should empower their teams to try the smallest possible experiments in a “build, test, learn, repeat” cycle. And by experiment, I don’t mean a £50,000 pilot. I mean: what can you test in two days with about £500? Some readers will recognise this as a paraphrasing of the Lean Start-up Method. But it’s as applicable to councils as it is to start-ups. The private sector uses this method to find product-market fit. In the public sector, we seek service-user fit.

To bring this to life, I invite you to spend just 2 minutes watching the video below. To my mind, it’s the single best video on the internet about the merits of this approach.

Watched it? Ok – let’s briefly imagine we’d taken a traditional local government approach to the same project.

The council might spend six months writing a frog-housing strategy and never get around to building anything. The council might assume it knew exactly what the frog wanted, commission a firm to build hundreds of frog houses, only to realise that not a single amphibian would ever want to live in one. The council might see the possum and rapidly invest in mitigation measures to avert the threat, which turned out not to exist. And the council would almost certainly never factor in that there might be unplanned users (the baby frogs and the possums) and miss the chance to cater for their needs.

I’m exaggerating for emphasis, but hopefully you take my point.

Every time we try to guess the big end solution, we will almost certainly fail. Not because of any lack of skill or intelligence, but because the world is simply incredibly complex. Instead, we must navigate our way through to the right answer, one tiny step at a time.

2 – Use the full toolkit

In the face of huge challenges, what do we want to be able to say about the tools and methods that councils use to respond? I assume we want them to have the largest possible toolkit at their disposal.

Yet often this doesn’t happen.

When councils approach change programmes, it’s common to see them take place in domain silos. A people initiative here. Some service design over there. Data is talked about by itself. And (a flaw in almost every digital transformation programme that has ever gone wrong) we change IT systems as though tech exists in its own vacuum.

Important message #1: People, technology, data and process are interlinked and interdependent. It’s almost impossible to change one without changing the others. Really effective change programmes work with all four. Example: No instance of artificial intelligence (AI) alone will solve the pressures in social care. But a new AI-enabled tool (tech), combined with deep user engagement (people), a new service model (process) and thoughtful use of information (data) might just make an impact.

Important message #2: the toolkit is so much larger than most teams think. At LOTI, we use our Service Innovation Cards to highlight that councils tend to unnecessarily limit themselves to working with 18 variables (see below in blue) when trying to improve a service. But there are at least another 6 variables (in pink) and 12 different roles councils can play (in yellow) to come up with quite radically different solutions. Check out the deck linked above for some inspiring, practical examples.

Leadership teams need to know about – and ensure their colleagues are able to use – all the tools available.

3 – Tackle big problems with more minds

Whenever the topic of innovation arises, it’s common for the narrative to be about great innovators; the hero-worship of individuals like Marie Curie and Steve Jobs. But it’s almost impossible to institutionalise a model that depends on individual greatness.

Great solutions to complex problems are more likely to arise with multidisciplinary teams.

One of the common mistakes we keep making as a sector is that we try to optimise only within siloed services. We hear of housing teams who have KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) about chasing late rent payments, while their colleagues down the corridor have KPIs about supporting people who are recently homeless – having fallen into rent arrears.

Silos exist for a reason. They help specialise and get things done. Yet optimising one service intervention without understanding the knock on consequences elsewhere misses the big picture.

One of the best ways councils can maximise their chances of developing solutions that can meet the complexity of the needs in their community is having multidisciplinary teams where each individual brings a different set of experiences and skills. Even better if those teams involve residents and service users.

I recently asked my network on LinkedIn “What’s your most compelling example of where a multi-disciplinary team developed a great solution that would never have occurred to a team made up of specialists in just one area?”.

You’ll enjoy reading their examples.

4 – Empower every employee to solve the problems in front of them

The other day I was travelling from my local train station. I needed to collect some pre-booked tickets from the machine. I tapped the touch screen. Nothing happened. I jabbed away for a few more seconds to no avail. Trying to be helpful, I thought I’d pop into the ticket office to report that it was broken.

“Just in case no one’s yet reported it, just wanted to let you know your ticket machine’s touch screen doesn’t seem to be working,” I told the man behind the ticket counter.

He gave me a rye smile. “Oh, that hasn’t been working for almost a year now,” he replied. “I’ve reported it up the chain, but no one ever gets back to me.”

“And that’s ok?” I was left wondering.

I returned to the platform to see customer after customer tap the ticket machine screen in increasing frustration. An annoyance for some, a complete barrier to travel for others who weren’t able to use an app.

So here was an employee – the public face of his organisation – who was apparently completely disempowered to fix or secure help to solve an obvious problem that was causing pain for his customers and harm to his organisation’s reputation.

I invite every council leadership team to ask themselves: is there any part of your organisation where staff could ever find themselves in that position?

It’s common – and understandable – for organisations to place responsibility for improvement on large change initiatives driven by management. Yet management teams are often distant from the immediate user experience such that they are not well placed to see obvious, small changes that could cumulatively make a massive impact. This is not a failing of those individuals. Blind spots are inevitable in any large organisation.

So how should they respond?

Empower every employee to fix, or get help to solve, the problems in front of them.

Innovation should not just be about large initiatives, but the micro, 1% incremental improvements that collectively sum up to make a huge difference. Many readers will recognise this as the field of Continuous Improvement. I’ve written more about that in one of my recent blogs.

5 – Create the conditions for innovation to happen

Let me finish by talking about two leadership behaviours that can help innovation thrive – and where their absence hinders it.

The first is to hold space for uncertainty. Nothing’s surer to kill innovation than leaders requiring teams to spell out exactly what the solution will be in advance, and to provide line-item budgets for the whole financial year before that year has even started.

Why? Because such demands make it almost impossible to experiment. They incentivise staff to engage in a collective game in which we pretend these things can be known in advance. Inevitably, we end up with project plans based on false and untested assumptions: key ingredients in why so many big change programmes run over time, over budget and still fail to deliver the desired results.

Some of these traditional leadership behaviours are borne out of an understandable desire to manage risk, the perception being that experimentation is risky.

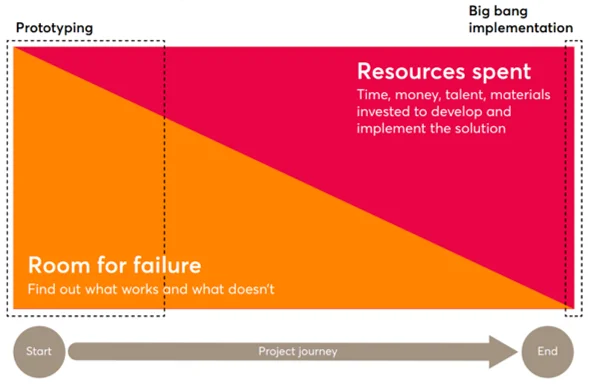

But the reverse is true if those experiments are conducted well. It is far less risky to spend a couple of weeks and £2,000 running micro experiments to test assumptions (see Habit 1) and establish what doesn’t work than it is to discover the flaws at the end of a long project. So long as each experiment is part of a build-test-learn loop, there is no point in the process where significant money has been spent on something that stood no chance of working. The diagram below from Nesta encapsulates that nicely.

Source: Nesta Playbook for innovation learning

The second thing leaders can do is to set a clear vision of what outcomes – what preferred futures – they want to achieve. Starting with the end in mind is at the heart of LOTI’s outcomes-driven methodology. It helps ensure that the experimental approach outlined in Habit 1 above has direction. Without a destination in mind, experiments risk becoming endless trial-and-error, rather than trial-and-improvement. Like a sailing ship tacking into the wind towards a desirable destination, we need to constantly course correct otherwise we risk ending up far off course.

In this approach, leaders can judge projects not on false promises of what the complete solution looks like, but on how well and how quickly they are learning what a plausible path to the desired destination looks like.

Conclusion

I’m a strong believer that local government has no choice but to innovate. But innovation shouldn’t mean placing giant bets on huge change programmes and expensive pilots. Instead, practicing the 5 habits above can help councils navigate change and bring new ideas to life in a responsible, motivating and more effective way. Only local government leaders can create the conditions for such habits to thrive.

Do you agree? As always, I welcome your comments, ideas and suggestions. Please comment on LinkedIn or get in touch at contact@loti.london.

Eddie Copeland