LOTI Sandbox in Adult Social Care: Prototypes

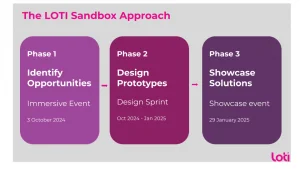

The LOTI Sandbox in Adult Social Care was an experimental approach that took place between October 2024 and January 2025. It was a holistic approach that brought together stakeholders from across the entire health and care system to explore potential innovations across technology and data solutions.

The LOTI Sandbox initiative consisted of three main phases:

- First, the immersive event used role-playing to bring care challenges to life through the simulated journeys of two individuals needing different types of support. This helped us identify opportunity areas and ideas for solutions.

- Second, our design sprint comprising five sessions that enabled multidisciplinary teams to transform these opportunities and early ideas into tangible prototypes that solved real needs and looked at the entire system rather than any one organisation, breaking down the traditional silos.

- Finally, a showcase event enabled us to use role play to show the impact of these prototypes in the lives of real people needing care and support.

The long-term vision is to establish a permanent physical space where borough officers can come together to test new products and services through prototyping and simulations.

More importantly, this methodology can be applied to any city-wide issue, including climate change, housing, children’s social care etc.

The six prototypes we developed with the support of borough and health practitioners, suppliers and innovation leads are as follows:

1.Care Buddies: A volunteer programme pairing individuals needing care with local people equipped with the skills and knowledge to help navigate the system and provide support.

The problems it solves

- Lack of early support that leads to health crises and worse health outcomes.

- Providing the right support at the right time. Family and friends want to be supportive but may not often know how to help or what’s most valuable.

- Online access to services. Digital exclusion particularly impacts the elderly and those without basic digital skills.

How we developed the prototype

The idea emerged from our first design sprint where participants role-played different community scenarios. Participants described how many people actually had willing friends and family who may not have an understanding of social care themselves in order to know how to help. Rather than creating only a new volunteer matching service, the group included increased structure and support for these existing relationships.

During our “Postcards from 2030” exercise, participants envisioned a future where community support was more formalized without being bureaucratic. A social prescriber in our sprint shared insights about what makes volunteer programs sustainable, sparking the idea to develop structured support packs and clear boundaries.

We’re aware that other similar initiatives, such as Integrated Neighbourhoods and others, are being tested elsewhere in the UK, seeking to involve community support to prevent the escalation of needs.

2. Plan My Care: A template form helping individuals plan for their future care and support needs.

The problems it solves

- Lack of planning of future care and support needs in a structured and consistent way.

- Reliance on people needing care having to recall and repeat the same information multiple times.

- Lack of contextual information as well as specific care preferences by emergency services and others.

How we developed the prototype

The inspiration to structure this solution like a birth plan came from an early discussion in the design sprint when a participant pointed out the stark contrast between how structured and supportive birth planning was compared to later life care planning.

Our shift from forms to conversations emerged during a group discussion in the second sprint. A mix of participants – from service designers to social care staff – shared stories of how forms often created barriers rather than solutions. One care manager described how their most valuable insights came from casual conversations with families during admission, rather than from filled-out paperwork. This resulted in the conversation cards that we designed for the day, based on work done by Dr. Atul Gawande in having better conversations with patients planning end of life care.

The concept of ‘trigger moments’ in which care planning might start up emerged during a “Postcards from 2030” exercise, where participants imagined future scenarios for people drawing on and delivering care support. A participant in the group suggested linking care planning prompts to existing resident touchpoints with local government – an insight that might have been missed without council staff with frontline experience in the room.

This process revealed that the Universal Care Plan is designed to support the planning of care and support pathways, providing individuals with choice and practitioners with better view of people’s preferences and needs.

3. Care Collaborators: A training programme for health and social care staff to develop holistic knowledge and provide personalised advice on navigating care systems.

The problems it solves

- Missed opportunities for signposting to local support.

- Increased complexity of care needs/intensity of crisis due to lack of early support.

- Siloed working across the health and care system including health, local government and community services.

How we developed the prototype

This solution emerged from a powerful insight shared by a former nurse during our design sprints. As we worked with the health and social care system map, she reflected on her time as a nurse, realising that she had never had a strong understanding of the wider health and social care system beyond her immediate role. More importantly, she noted that there hadn’t been any incentive or support or capacity for her to help patients navigate what happened after they left her care.

This personal reflection sparked a broader discussion about how professionals across the system often work in silos, unable to support people in navigating the wider system even when they want to. The solution evolved from this recognition that we needed to support health and social care staff see beyond their own part of the system to better support residents.

4. Care Compass: A simple, plain-language web portal providing clear and accessible information about Adult Social Care options and pathways for residents and carers.

The problems it solves

- Lack of easy access to information about local care and support services for carers and people needing care.

- Use of jargon, and complex language.

- Lack of understanding of care options.

How we developed the prototype

This solution emerged from a powerful insight shared by a former nurse during our design sprints. As we worked with the health and social care system map, she reflected on her time as a nurse, realizing that she had never had a strong understanding of the wider health and social care system beyond her immediate role. More importantly, she noted that there hadn’t been any incentive or support for her to help patients navigate what happened after they left her care.

This personal reflection sparked a broader discussion about how professionals across the system often work in silos, unable to support people in navigating the wider system even when they want to. The solution evolved from this recognition that we needed to support health and social care staff in working beyond their own part of the system to better support residents.

We’re aware that there are many solutions in this space that address the issues of lack of clear signposting or plain language information.

5. My-ghty Magnet: A smart fridge magnet with a QR code storing vital health and care information, instantly accessible by paramedics, care workers, or family in emergencies.

The problem(s) it solves

- Lack of access to health and care needs information in case of emergency hospital admissions.

- Delays in providing the right care (e.g. medication) and support to urgent hospital admissions owed to access to information by multiple agencies.

- Lack of communication between different agencies involved in an individual’s care.

How we developed the prototype

The spark for this solution came during a group discussion when a participant brought up the “Message in a Bottle” scheme – where people store their medical information in a plastic bottle in their fridge for emergency services to find. This existing practice of using the fridge as an information point led us to think about how we could modernize and expand this concept using digital technology.

A key breakthrough in our design came when the group flipped the traditional approach to data sharing. Instead of waiting for institutions to sort out complex data-sharing agreements, participants suggested putting control in residents’ hands. Early consultation with our in-house information governance expert helped us understand how to make this legally workable, including finding sleek solutions like verifying paramedics by simply checking if an ambulance was dispatched to the address rather than requiring complex NHS email verification.

The solution became even more powerful when participants realized it could connect with other prototypes being developed in the room. For example, the information could be initially captured through Plan My Care, with an AI tool helping to surface relevant details based on the emergency situation. This kind of integration only emerged because we were developing multiple solutions in parallel.

6. Care Flow: A system that streamlines referrals to social care with behavioural nudges, real-time updates, and AI-powered backend tools for triaging and managing messages efficiently.

The problem(s) it solves

- Reduced no of incorrect/incomplete referrals.

- Delays and increased social care services costs in processing referrals.

- Lack of updates on progress.

How we developed the prototype

During our system mapping exercise in the sprint, having social care team members map out their daily workflow alongside other participants helped visualize how information moves through the system. This activity revealed how social care often becomes a central hub for support requests, with team members dedicating significant time to investigate incomplete referrals, followed by assessing and coordinating responses.

An activity using the ‘Now/Next/Later’ framework in the design sprints brought up a particularly rich discussion because we had both frontline staff and digital suppliers in the room. Social care practitioners could describe their current challenges and processes in detail, while technology partners who had built similar systems elsewhere shared insights about how digital tools could help guide and organize incoming requests more effectively.

Building on these conversations, we explored how technology and concepts from behavioural science could support better information gathering upfront, a key pain point that emerged from the Postcards from the Future activity. The solution evolved into a comprehensive system beyond the initial form that could use AI to intelligently support the process of prioritising referrals based on existing information from different sources, as well as automating communications and updates to the referring organisation and the individuals being referred.

Here’s what we learned about:

- The core elements of the process:

- Immersive role-play – It completely changed the thinking and conversations around service delivery. Bringing to life via role play the different care individual journeys helped the audience empathise with individuals’ lived experiences.

- Holistic approach – Bringing together the whole heath and care system helps to break the organisational silos and support practitioners to think about holistic patient experiences beyond organisational boundaries.

- Dedicated space and time – Having a dedicated space and time to take a step back and reflect on our practices and the way we deliver services, has been the most common feedback from participants in this process.

- Solutions:

- Multi-disciplinary approach – Involving frontline social care and digital practitioners from health and local government as well suppliers and academics was incredibly useful for capturing the nuances of challenges and helped to spur thinking about solutions that are much more than a sticking plaster.

- Iterative co-design – The rapid design sessions helped us identify opportunities and bring them to life as prototype solutions, iterating them at speed.

- Existing solutions – Another benefit of running this process and taking a systems view is that we unearthed solutions that either were already in development or are currently being tested. As a result, we created this resource for the LOTI social care and digital innovation/transformation community, to support their thinking on digital solutions.

This approach consistently breaks down siloed thinking by taking a systems approach, brings to life real experiences, and engages stakeholders in collaborative problem-solving and co-design of solutions.

LOTI is now in conversations with several partners to identify funding opportunities for testing these solutions in real life.

Please visit the LOTI website, for further information.

Genta Hajri

Anjali Moorthy